An evidence-based critique of "An Evidence-Based Critique of the Cass Review"

There's no evidence that opposite-sex hormones help

Essay by ML.

Main Takeaways (the TLDR version)

A new report from the Integrity Project at Yale Law School criticizes the Cass Review's findings on gender-affirming care (GAC), particularly its conclusion that the evidence supporting GAC is weak. The Review commissioned the University of York to undertake a series of independent, peer-reviewed systematic reviews to better understand the existing evidence base. Systematic reviews are considered at the top of the hierarchy in evidence-based medicine. The systematic reviews conducted by the University of York examined 237 papers from 18 countries involving 113,269 children and adolescents.

The Yale report argues that the Cass Review overlooks positive outcomes of GAC, such as improved body satisfaction, appearance congruence, quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and mental health, as well as reduced suicidality, providing as evidence two studies: Chen et al. (2023) (the “longest and largest study to date”) and Tordoff et al. (2022). The report also claims that the hormone treatments lead to improved mental health by targeting appearance congruence. We test the validity of these claims by reviewing these studies in detail.

Chen et al. examined psychosocial functioning in transgender youth after two years of opposite-sex hormone therapy. However, the study did not report findings for 6 out of 8 measurement outcomes stated in its protocol. The males in the study did not experience any improvement in their mental health, while the females showed negligible improvements, even while both underwent significant appearance congruence (and two of the subjects, all of whom were screened for the presence of serious psychiatric symptoms, committed suicide during the first year of the study). Since strong placebo effects are routine with psychotherapeutic medicine, the lack of improvement raises serious questions about medicalization using opposite-sex hormones, which have lifelong effects.

Tordoff et al. investigated the effects of opposite-sex hormones on depression and suicidality. Significant flaws in the study include the fact that the treatment group showed no improvements at all and an 80% dropout rate in the control group. These fundamental drawbacks in the study’s design undermine the validity of its conclusions.

It is abundantly clear that there is no good evidence to push medicalization using opposite-sex hormones on children and young adults suffering from gender-related distress. It also shows the complete lack of scientific process in the world of gender-affirming care. It is unforgivable that bad-faith actors continue to actively indulge in such reprehensible misinformation that preys on the insecurities of vulnerable young people, especially after the most comprehensive review of the evidence to date.

“Why Is the U.S. Still Pretending We Know Gender-Affirming Care Works?” asks a new (and extremely well-researched piece) by Pamela Paul in the New York Times. Good question, Ms. Paul. A part of the puzzle is that there is an active agenda from activists and clinicians who would say anything – anything at all – to discredit the Cass Review, a four-year endeavor carried out at the behest of the NHS in the UK that looked at 237 papers from 18 countries, providing information on a total of 113,269 children and adolescents on “gender-affirming care” (GAC). The latest such example is a new report from the Integrity Project at Yale Law School (no, that’s not a typo) that critiques the Cass Review for having found that the entire edifice of GAC is built on extremely “shaky foundations.” The report is non-peer-reviewed, and even though they do not declare any conflict of interest, some of its authors have published their own studies that were rated poorly by the Cass Review.

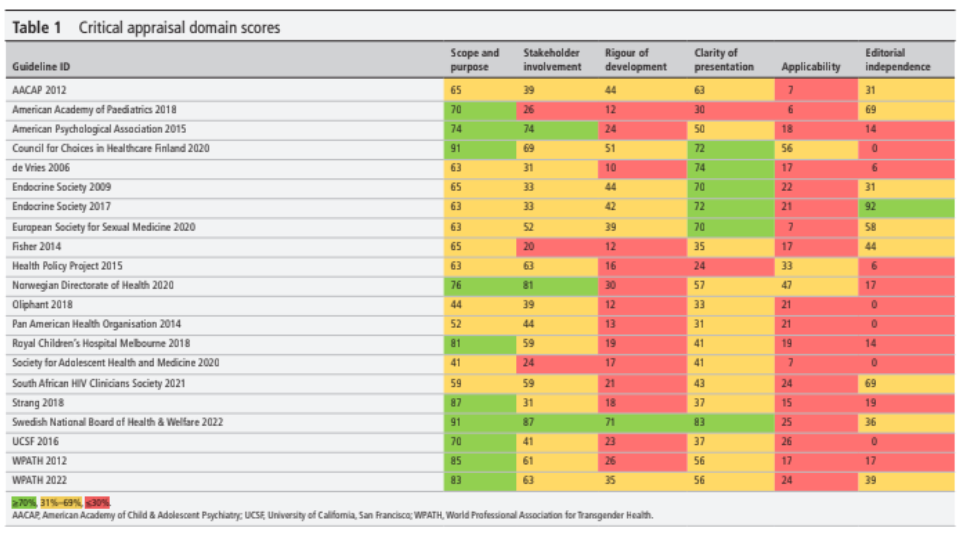

In its initial sections, the report ferrets through each and every sentence from the Cass Review that its authors – who I will refer to as McNamara et al. hereafter – can somehow agree with, if not in spirit, then in the letter, perhaps to show that they are being reasonable in trying to find common ground. For example, “The Review explicitly notes that, “for some, the best outcome will be transition” (p 21) while also acknowledging, as the WPATH Standards of Care and the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines do, that gender-affirming medical interventions are not appropriate for all transgender adolescents.” Never mind that one of the systematic reviews conducted on the behest of the Cass Review explicitly looked at the quality of the different guidelines and found that not only were the multitude of guidelines from different medical associations across the world essentially repeating the guidelines of the Endocrine Society (from 2009) and WPATH SOC 7 (from 2012), “[t]he two guidelines also have close links, with WPATH adopting Endocrine Society recommendations in its own guideline and acting as a cosponsor for and providing input on drafts of the Endocrine Society guideline.” And that these two mothership guidelines were rated very poorly within that systematic review.

This is the same WPATH that commissioned the Johns Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center to conduct a series of systematic reviews of the evidence behind GAC. When the review team found none, WPATH prevented them from publishing their findings.

Not only that but after these inconvenient findings, WPATH put into place a Kafka-esque set of requirements for any systematic review it commissions from then on. First, the reviewers had to pre-clear the proposal so that its conclusions coincided with WPATH’s views (so, the “review” of the evidence would merely rubber-stamp WPATH’s predetermined views on what transgender medical care should be). Second, WPATH’s members had to be included in the design and drafting of the content. Finally, WPATH had to explicitly clear the final manuscript when it was ready for submission to a journal. And yet, after all that, the authors still had to include a sentence that “the author(s) have acknowledged that the authors are solely responsible for the content of the manuscript, and the manuscript does not necessarily reflect the view of WPATH in the publication.”

As a result, only two of thirteen reviews ever saw the light of day. Consider one of them – “Hormone Therapy, Mental Health, and Quality of Life Among Transgender People: A Systematic Review” – whose conclusions seem to indicate that the opposite-sex hormones had salubrious effects on mental health. However, if you read through the review (which WPATH very much hoped – correctly, as it turned out – that most journalists would not), you will immediately see that such conclusions are unwarranted since the authors only found “low” and “insufficient” evidence for administering these opposite-sex hormones.

All the study protocols for these reviews were pre-registered in PROSPERO, which is the “international prospective register of systematic reviews” maintained by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) at the University of York, and which, over the past 20 years, has completed over 200 systematic reviews covering a wide range of healthcare topics. (The Cass Review tapped into researchers from this very same University of York to conduct their series of systematic reviews on gender care for children and adolescents.) Researchers register their study protocols in advance “to help avoid duplication and reduce [the] opportunity for reporting bias by enabling comparison of the completed review with what was planned in the protocol.” The last few words – “what was planned in the protocol” – are important, as will become clear later.

But let me not get sucked into critiquing each and every aspect of this Yale Law report – there are so many bones to pick with this critique that it would be exhausting (which I think is one of its principal aims: to overwhelm the readers with a deluge of words that sound somewhat medically informed, and maybe spike some ongoing court proceedings along the way). Instead, in this post, I will concentrate on one of the main complaints of McNamara et al.against the Cass Review: that it “does not describe the positive outcomes of gender-affirming medical treatments for transgender youth, including improved body satisfaction, appearance congruence, quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and mental health, as well as reduced suicidality.” (p. 10) The report is liberally sprinkled with citations (over 100 of them) – the quality and their germaneness should be the subject of another review – but this specific and hugely consequential statement is bookended by not even a single citation. Instead, we have to hunt for them.

(For those looking for a general rebuttal of the series of claims in this Yale Law report, a very nice introduction is the series of FAQs that Dr. Cass and her team continue to update on their official website to address the misinformation about the Review. Some of the questions answered include:

Did the Review set a higher bar for evidence than would normally be expected?

Did the Review reject studies that were not double-blind, randomized control trials in its systematic review of the evidence for puberty blockers and masculinizing/feminizing hormones?

Did the Review reject 98% of papers demonstrating the benefits of affirmative care?

The short answers are No, No, and No, but the good doctor provides much longer answers. She could not have anticipated everything that a group of people with mischief on their minds could have dreamt up, but you will be on a much firmer footing when someone asks you about “that Yale Law report.”)

To be sure, the Yale Law report complains (a lot) about the various studies that have looked at the evidence of benefit from GAC, specifically the effect of opposite-sex hormones. The York University team indeed reviewed all these studies (and then found them wanting in terms of quality and certainty of the evidence), but McNamara et al. still cannot believe why they were found lacking (hint: go through the Cass Review team’s research methodology or maybe just go through the FAQs that specifically talk about their methodology). However, McNamara et al. reserve their ire for Cass’ failure to look at the pathbreaking – groundbreaking? superlative? most awesome? – research that is being done in the United States with the help of tens of millions of dollars of grants from the government: “Highly impactful studies, such as the longest and largest study to date on gender-affirming medical treatments in youth, received only passing mention… This [i.e., the study’s conclusions per the Cass Review] fails to engage with the study’s core findings that such treatments lead to improved mental health by targeting appearance congruence.”

The “longest and largest study to date” – not my words, they are McNamara et al.’s. So, in their eyes, the gold standard.

Also in their words: “such treatments lead to improved mental health by targeting appearance congruence.” This is important because many adolescents, especially the ones whose gender-related distress did not start early in childhood, often have an inchoate sense of anxiety and depression, which is then later affirmed online to be gender-related. If the study truly finds that these hormone treatments lead to improved mental health, that’s welcome news. We will shortly look at what the evidence in this study actually says.

Which is this “longest and largest” study? Written by nine authors – D. Chen, J. Berona, Y.M. Chan, D. Ehrensaft, R. Garofalo, M.A. Hidalgo, S.M. Rosenthal, A.C. Tishelman, and J. Olson-Kennedy – it is titled “Psychosocial Functioning in Transgender Youth after 2 Years of Hormones, and was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 2023. (Note that Johanna Olson-Kennedy, one of the co-authors of this “longest and largest” study, is also one of the co-authors of the Yale Law report.)

McNamara et al. are also aggrieved that the Cass Review disses another American study, specifically mentioning it by name in the main text: “Of note, Tordoff et al[.] was excluded due to scoring low on the authors’ adapted NOS [Newcastle-Ottawa Scale]. However, this study shows statistically significant reductions in depression and suicidality.”

And that’s about it. If we have to look at specific studies that have seemingly gotten short shrift from Cass despite proving the benefits of opposite-sex hormones, these are the only two studies McNamara et al. mention by name. The York University team covered the other studies that the Yale Law group complained about, but the evidence in those studies was found to be of (mostly) low quality. More importantly, because of the absence of high-quality studies and “heterogeneity in study design, intervention, comparator, outcome, and measurement,” it was impossible to state with any certainty what the effects of opposite-sex hormones (or for that matter, GnRH analogs) might be – which is why, just like the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, the Cass Review recommended that hormone treatments should only be provided under a research framework in order to develop a stronger evidence base.

It needs to be emphasized that even though a particular study might be rated “moderate quality,” given the variability of pertinent factors outside the study's environment, it is difficult to extrapolate what its findings mean for the general population. This is apparently lost on the Yale Law group, given their insistent focus on the evidence from individual studies. Studies can have many types of flaws (we have listed some of the common ones here), which is why they need to be graded independently on their quality – instead of forcing the review team to reach a desired conclusion, as WPATH did. Furthermore, one specific study will probably be looking at just a sample of cases within a particular clinic (or maybe a few clinics). However well-designed that study might be, there is always a probability of error, and because the sample from that clinic will be different from other clinics, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to extrapolate the results of that study to the general population. The variability of the patient experiences, the quality of the medical staff, the experience of the doctors within the clinic, and the protocols that are followed before prescribing medicine – these are just a few of the many aspects that might differ from one clinic to another. Different studies investigating the same phenomenon often come to opposite conclusions – one of the dominant themes observed by the Cass Review team. That is where a good systematic review comes in: it considers the totality of the evidence across all studies – the good and the not-so-good, giving more credence to the findings from the former than those from the latter – to determine what we actually know. This is exactly the reason why systematic reviews are considered to be at the apex of the “evidence pyramid,” even higher than individual randomized control trials.

Looking at the totality of the evidence, Dr. Cass found it “remarkably weak.” (She also went on to say, “Adults who deliberately spread misinformation about this topic are putting young people at risk, and in my view, that is unforgivable”). Dr. Cass concluded that it is essential to guard against the “creep of unproven approaches into clinical practice” (page 45, Cass Review). As the Economist has pointed out, this is hard in a politicized environment, and it will be even “harder in health systems where private doctors are paid for each intervention, and thus have an incentive to give patients what they ask for [hello, United States!]. Nonetheless, it is the responsibility of medical authorities to offer treatments based on solid evidence.”

Let’s now look at these two studies that apparently show all the benefits of opposite-sex hormones, including “improved body satisfaction, appearance congruence, quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and mental health, as well as reduced suicidality,” actually say. First up: Chen et al., 2023. Considering how much shade McNamara et al. throw at the Cass Review team for supposedly not fully understanding what the literature meant, it is worthwhile to inspect the evidence they consider the gold standard.

We first note that Chen et al. did not report findings for 6 of 8 measurement outcomes – gender dysphoria, trauma symptoms, self-injury, suicidality, body esteem, and quality of life – they announced in their study protocol. You will remember that one of the objectives of having a registered study protocol at inception is to “reduce [the] opportunity for reporting bias by enabling comparison of the completed review with what was planned in the protocol.” Stated in another way, it allows us to see whether the research team showed what they planned to look at when they began their study or were busy HARKing (Hypothesizing After the Results are Known).

Let’s just say this isn’t very reassuring, even before we have begun to review the paper.

Now, you don't get to see the study protocol in the paper itself. You have to download the protocol document at the bottom of the page as part of the supplementary material. When you download the study protocol, take a few seconds to also download the supplementary appendix. It will be useful later on.

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, here’s journalist Jesse Singal using some artistic license to illustrate what their results should have looked like:

I will talk about the column on the right – effect size – later.

This next image, also from Singal's post, is a screenshot of the protocol document (page 43). The left-hand column shows all of the outcome variables the research team measured throughout the study — at the start and then at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. The right-hand column shows the measures used to quantify the outcomes. Of the more than two dozen outcome variables measured, the researchers report only five:

Thus, even before getting into the research findings, there are two giant red flags: dropping 75% of the outcome variables that the researchers said that they would measure (and instead measuring something else and then insisting that that is what they were trying to measure, anyway) and reporting results of a small fraction of the things they did measure.

On to the data in the outcome variables reported in the published paper. For males who received opposite-sex hormones – estrogen – there was no improvement in depression, anxiety symptoms, or life satisfaction scores. Estrogen did not change their positive affect (the extent to which an individual subjectively experiences positive moods such as joy, interest, and alertness) either (and this is true for either sex). In fact, other than appearance congruence – i.e., how closely a participant's appearance mirrored their idea of what they “should” look like as the opposite sex – estrogen did not do anything at all for males. The authors state that clearly in the paper itself:

You would have thought that such a significant result would have been mentioned in the paper’s abstract (which is what most people would read, if anything), but instead, the authors try to hide these inconvenient findings. They hypothesize that the lack of improvement may be due to the long delay before the changes to the physical appearance of the boys fully take effect: “estrogen-mediated phenotypic changes can take between 2 and 5 years to reach their maximum effect.” Unfortunately for them, their hypothesis is explicitly repudiated by their own data: the male-to-female subjects improved significantly in terms of “appearance congruence” – in fact, as well as the girls:

(From the Supplementary Appendix, page 25, panel S3-A. The blue line shows the average appearance congruence scores for females, and the orange line is for males).

Having dropped 6 of the 8 measurement outcomes from their study protocol, the authors make a huge deal about how this appearance congruence is the primary outcome after all, dammit. It is a sentiment that Johanna Olson-Kennedy carries over to the Yale Law report, where they state: “This [i.e., Cass’s summary of the paper’s conclusions] fails to engage with the study’s core findings that such treatments lead to improved mental health by targeting appearance congruence [italics mine].”

If these hormones target your body's appearance, that’s the least you should expect them to do: change your appearance! But, more significantly, if, after these considerable changes to their bodies’ appearance, there were no changes to the boys’ depression, anxiety, or life satisfaction scores, then – pardon my French – what the eff are all these interventions for? Johanna? Meredithe? Jack? Anybody else?

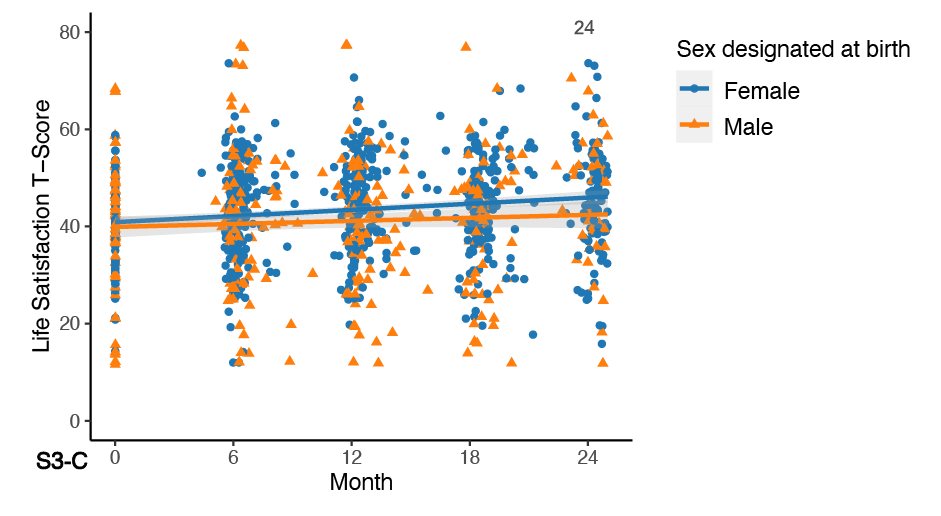

OK, fine. The results with the boys were a bummer. But one could argue the girls saw improvement, right? Well, for that, you will have to pore through page 25 of the supplementary appendix once again. Panel S3-A (shown earlier) represents appearance congruence. We see a significant jump in appearance congruence after 2 years on opposite-sex hormones, as opposite-sex hormones are wont to do. But consider the panel most flattering to the results Chen et al. would want to portray – S3-D, which shows depression scores starting at the beginning and all the way up to 24 months on opposite-sex hormones.

The orange line (average depression score for males) shows no change – the authors have already told you that. The blue line (for females) dips somewhat. These lines are the average depression scores of the cohort on hormones on the Beck Depression Inventory-II scale. Scores on this scale range from 0 to 63: scores of 11-16 signify mild mood disturbance, 17-20 borderline depression, 21-30 moderate depression, 31-40 severe depression, and scores over 40 signify extreme depression. The average depression score at the beginning for the girls is just above 15 – i.e., on average, these girls started off having mild mood disturbances. These are children between 12 and 20 (see Table 1 in the main text). Have you seen teenagers without any mild mood disturbances? Starting at an average depression score of 15, those scores for the girls, after two years on opposite-sex hormones, ended up between 12 and 13 (the exact numbers aren't available since the descriptive stats – Table S6, for example – do not break down results by sex).

Stated differently, the girls had – on average – mild mood disturbances to begin with, and... they still had mild mood disturbances after two years on opposite-sex hormones. Remember the assertion by McNamara et al. that “such treatments lead to improved mental health by targeting appearance congruence?” We have appearance congruence – in spades – but where exactly is the improved mental health for these children, Meredithe?

Don’t just take my word for it. Look at the “effect size” of these scores (the right-hand column of Figure S5 on page 13 of the supplementary appendix). The effect size tells us whether the changes in the data are practically meaningful. (To understand why effect size is important, take a look at this paper titled “Using Effect Size—or Why the P Value Is Not Enough”: “With a sufficiently large sample, a statistical test will almost always demonstrate a significant difference unless there is no effect… very small differences, even if [statistically] significant, are often meaningless.” This is where the effect size comes in – it tells us whether this difference is of any practical significance whatsoever.) As Chen et al. mention in the note below Table S5, effect sizes between 0.2 and 0.5 are considered small – and other than appearance congruence, the effect sizes of all the other output variables are small (and positive affect, as I mentioned earlier, is not even statistically significant – for either sex).

Still, as every experienced statistician knows, not everything is captured in the numbers. Context is important. Even more so with patient-reported outcome variables. This context is covered in an exhaustive Reddit post on the Chen paper (as well as the Tordoff paper – more on that later). The author is an ABPN (American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology)-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist with many years of experience. As mentioned in the post, the lack of any improvement (among boys), given the huge change in appearance congruence scores, is extremely problematic: “If a change from 3 [neutral] out of 5 to 4 [positive] out of 5 is not enough to change someone’s anxiety and depression, this is problematic both because the final point on the scale may not make a difference and because it may not be achievable.”

What about the girls? Well, here’s the thing: placebo effects in psychiatric medicine have routinely been very strong. The Reddit poster gives two examples of the strong placebo effects in psychiatric medicine – “In the original clinical trials for Trintellix, a scale called MADRS was used for depression, which is scored out of 60 points, and most enrolled patients had an average depression score from 31-34. Placebo reduced this score by 10.8 to 14.5 points within 8 weeks (see Table 4, page 21 of FDA label). For Auvelity, another newer antidepressant, the placebo group's depression on the same scale fell from 33.2 to 21.1 [a change of 12.1 points] after 6 weeks (see Figure 3 of page 21 of FDA label).”

Compared to these double-digit changes that are routinely observed with placebos, the changes in the depression scores (2 points and change on a 64-point scale) after two years of opposite-sex hormone therapy in the girls are minimal – statistically significant perhaps, but clinically meaningless. It is no wonder that the Beck Depression Inventory-II has such wide ranges for the different classifications of depression – patients cannot distinguish between minute changes on a man-made scale in their day-to-day lives.

More alarmingly, the minuscule improvements also lead to some more uncomfortable questions – if large placebo effects are routine in psychiatric medication, why are we seeing so little differences after opposite-sex hormones? Did these hormones harm the children’s psychiatric health, and would we have seen larger improvements if the children were not subjected to the hormones at all? Unfortunately, we cannot answer such questions, even from “the longest and largest study,” because there is no control group.

Could there have been some kids among the 315 who became much better after hormones? Well, maybe – or maybe not. Chen et al. do not comment on individual cases. But that is not what evidence-based medicine is all about – a few anecdotes do not data make. I am sure we can find some people who swear they work phenomenally after taking cocaine, but our doctors don’t prescribe cocaine (well, not yet 🤞– it is American pharma we are talking about, after all). And while we are discussing individual cases, here’s something that should also be addressed – the fact that the Cass Review “explicitly notes that “for some, the best outcome will be transition” (something McNamara et al. mention almost breathlessly), such a statement is as relevant to the overall population of gender-dysphoric children and adolescents as “for some people, cocaine might be beneficial.” Sure, there might be – the human body and mind are infinitely complex – but how do we correctly identify these children? As Dr. Cass mentioned in an interview, “We're certainly not saying that no one is going to benefit from these treatments, and I myself have spoken to young people who definitely do appear to have benefited. But what we need to understand is what's happening to the majority of people who've been through these treatments, and we just don't have that data. I certainly wouldn't want to embark on a treatment where somebody couldn't tell me with any accuracy what percentage chance there was of it being successful, and what the possibilities were of harms or side effects.” (And please don’t try to pull some “transcendent sense of gender” that “goes beyond language” nonsense on us, Jack.)

Anyway, back to these changes after the opposite-sex hormones. These extremely slight and practically meaningless changes (other than appearance congruence) cry out for proper studies with relevant control groups. One could understand that not handing out hormones to a control group would be unethical if these adolescents had significant reductions in depression, anxiety, suicidality, gender dysphoria, etc., after hormones (as Turban tried to imply in his recent PBS interview). But that is emphatically not the case.

It is also relevant here to mention that Chen et al. screened the children who would be eligible for the opposite-sex hormones (see the study protocol for the details), unlike how they are being handed out in other pediatric gender clinics or Planned Parenthood centers.

Screenshot from Planned Parenthood

These were generally well-adjusted children who were screened in advance to make sure that the ones with severe psychological distress were excluded. They were looked after by multi-disciplinary teams in the four best pediatric gender clinics in the country – something that is as common in the United States as a snowflake in July in downtown Phoenix. They still ended up with two suicides among the 315 kids within the first 12 months (and nearly a third of their participants had dropped out of the study by the 24-month follow-up for who knows what reasons, despite the extensive attention and support these kids received: Table S2 on page 9 of the supplementary appendix). That rate of suicide is more than 24 times higher than what was observed among children in the NHS GIDS clinic, either receiving hormones or on the waiting list. The latest data from NHS England was published just a few days earlier, and the evidence shows a total of 12 suicides in 6 years among all children in England who were referred to the NHS clinics. Alongside the data, there is also a summary of the problems faced by these young people – mental illness, traumatic experiences, family disruption, and being in care or under children’s services, confirming yet again that multiple factors contribute to suicide risk in this group.

(It is irresponsible to sensationalize suicide, as many trans activists are wont to – in fact, the latest information on suicides among children under NHS England was published to repudiate some ugly and reprehensible rumors started by a legal campaign group, even when LGBT groups explicitly warn against spreading such rumors – but we do want to emphasize how mercifully rare suicide is among children suffering from gender-related distress. Even when this was established in the extant literature, the fact that an NIH-funded academic study could have started to show how hormones reduce suicidality – and the findings concealed when the data turned out to be inconvenient – shows how pernicious the effects can be when we allow our preferred beliefs to supersede scientific process.)

Let’s summarize what we know so far. Among the claims of McNamara et al. – “improved body satisfaction, appearance congruence, quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and mental health, as well as reduced suicidality” – we see appearance congruence for sure. But there is no real evidence of improved body satisfaction (unless you make the unfounded leap that appearance congruence leads to body satisfaction). Quality of life was not measured (this is distinct from life satisfaction, and the changes were once again practically non-existent, and – to remind the readers once again – the boys showed no change). As for the other outcome variables, as the other panels on page 24 (and the data in Table S5 on page 13) of the supplementary appendix show, there is no practical change. (S3-B shows the positive affect scores, S3-C shows the life satisfaction scores, and S3-E shows the anxiety scores over the 24-month period.)

Finally, “reduced suicidality” was not addressed by Chen et al., 2023 – even though they laid down “suicidality” as one of the outcomes they would measure in their study protocol (I imagine it might have been problematic after those two suicides).

So, where does the reduction of suicidality get measured? Why, Tordoff et al., 2022, of course! I remember someone mentioning this “study” as the zombie that refuses to die – killed many times, yet more than two years later, it still shambles along. For a synopsis, I will defer to the Reddit poster once again to outline its fundamental problems (which is why it was rated so poorly by the Cass Review, something that McNamara et al. apparently failed to understand): “This paper is widely cited as evidence for GAH [gender-affirming hormones], but the problem is that the treatment group did not actually improve. The authors are making a statistical argument that relies on the “no treatment” group getting worse. This would be bad enough by itself, but the deeper problem is that the apparent worsening of the non-GAH group can be explained by dropout effects [italics mine]. There were 35 teens not on GAH at the end of the study, but only 7 completed the final depression scale.” Stated more simply, of the group that did not take hormones, 8 out of 10 were no longer being measured by the end of the study, and the conclusions about the group were made based on the remaining 2.

To quote Abbruzzese et al. (2023), “The spin of Tordoff et al. (2022) is dramatic.” As they pointed out, the Occam’s Razor explanation is that these children started to feel better and stopped coming to the clinic and that the highest-functioning untreated youth simply dropped out of the study – however, that is something we will never know for sure because Diana Tordoff and her co-authors never followed up with them. (Note to young people who want to become researchers one day – don’t be like Diana. Real research is hard. Getting credible data is hard. Taking shortcuts might enable you to get your paper published somewhere, especially if you want to cash in – literally – on the latest cultural fads. You might get millions in research grants or even become famous because your university does not understand what true research is. However, you will never become a researcher.)

If the Occam’s Razor explanation is correct, the conclusion we can draw is that for the overwhelming majority of children suffering from gender dysphoria who are in loving homes, doing nothing and letting them just grow up and become more comfortable with adolescence, the confusing emotions it brings, and their own sexuality would be the best course of action.

There you have it: all the evidence of the benefits of opposite-sex hormones that the Cass Review has apparently failed to consider adequately. To highlight how underwhelming this “evidence” is, let me quote one last time from the Reddit poster (italics mine):

“If we say we care about trans kids, that must mean caring about them enough to hold their treatments to the same standard of evidence we use for everything else. No one thinks that the way we “care about Alzheimer's patients” is allowing Biogen to have free rein marketing Aduhelm. [Interestingly, Adulhelm was approved by the FDA against the wishes of nearly every member of the Advisory Committee.] The entire edifice of modern medical science is premised on the idea that we cannot assume we are helping people merely because we have good intentions and a good theory. If researchers from Harvard and UCSF [and Northwestern and UCLA and USC] could follow over 300 affirmed trans teens for 2 years, measure them with dozens of scales, and publish what they did [as Jesse Singal mentioned, Chen et al. measured more than two dozen outcome variables, but when it came to reporting them, they HARKed], then the notion that GAH is helpful should be considered dubious until proven otherwise. Proving a negative is always tricky, but if half a dozen elite researchers [actually, nine] scour my house looking for a cat and can't find one, then it is reasonable to conclude no cat exists. And it may no longer be reasonable to consider the medicalization of vulnerable teenagers due to a theory that this cat might exist despite our best efforts to find it.”

A few additional observations before I conclude: Going through this entire Yale Law report, what I found interesting is how ingrained the culture of proceeding blindly in the absence of evidence is among these medical and other (one of the authors has degrees in economics and law) professionals – probably a result of the decades-long onslaught of the medical-industrial complex that has been described so aptly in John Abramson’s book Sickening. Doctors in the US are conditioned to intervene with something, anything, whenever they come across a symptom (restless legs syndrome, anyone?). It is a consumer-centric model of healthcare gone amok, where patients and their doctors rarely have the information to make informed decisions about their healthcare in a system guided more by business considerations and less by what is in the best interests of the patients. Which is why gender care in the United States is where it is today.

It is truly distressing to see how Meredithe and Co. think they have an ace up their sleeve when they mention GLP-1 receptor agonists (like Ozempic) that the AAP has now included in its treatment for obesity among children and adolescents. Instead of talking about the complicity of the AAP with the pharma industry by recommending starting with long-term (and expensive) medication with unknown effects and known risks of these new medications like thyroid cancer and pancreatitis, they embark upon a tirade of complaint – “The evidence on GLP-1s can be critiqued in many of the same ways that transgender healthcare is. GLP-1s in children have only been studied for 1-2 years. We do not yet know what the long-term impacts of profound weight loss in adolescence are on bones and disordered eating. Will they be able to enjoy food in adulthood? Can these medications ever be stopped without rebound weight gain?” In other words, “Why are we being held to a higher standard when so much of the research in pediatric medicine is so bad?”

To which my response is, “Ek-fucking-zactly, Meredithe!” The rest of the industry, including the pediatric medical-industrial complex, should be held to a higher standard. However, even inside that industrial complex, they put up a fig leaf of the scientific process. They employ control groups to test drug efficacy. If you read the paper that you cited, which lists the current guidelines from AAP to tackle childhood and adolescent obesity, you will find that the GLP-1 reference appears in a paper published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine (and funded by Novo Nordisk: feel free to include your necessary asterisks here). It is titled “A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Liraglutide for Adolescents with Obesity.”

Yes, among all this clusterfuck that is American health and healthcare (by one measure, ranked 69th in the world, lower than 58th-ranked Iran, a country where homosexuality is illegal but where clerics accept the idea that a person may be trapped in the wrong body and have a sex-change procedure with financial assistance from the state “to lead fulfilling lives”), and all caveats aside, there is a randomized, double-blind trial (and yes, Meredithe, I know what you are going to say, you cannot have a blinded trial with opposite-sex hormones, and Dr. Cass has talked about that already). That does not absolve either the AAP or Novo Nordisk of their sins. As Meredithe and friends have so admirably pointed out in their diatribe, we do not yet know the long-term impacts of profound weight loss in adolescence and on bones and disordered eating (there is data for just 56 weeks of treatment followed by 26 weeks of follow-up). We do not know if these children will be able to enjoy food for the rest of their lives (ask most adults on Ozempic – the answer is a resounding no). We do not know if there will be a rebound in weight gain once we stop these medicines. And we definitely do not know what the long-term effects will be: in just these one-and-a-half years of the study, a significant fraction in the treatment group had pretty consequential adverse effects. These are all very relevant and important questions, Meredithe! Which is why it behooves the American medical establishment to consider the questions you raise very strongly before approving such drastic interventions on children.

However, we know that expecting so much from an industry solely devoted to profit maximization is a pipe dream. But even in that world, there is some semblance of a scientific process. In your world of gender-affirming medicine, Meredithe, you don’t even have that.

DIAG team member ML was born and brought up in India. ML came to the United States for a PhD and became an academic somehow. When his son decided to identify as a transgender lesbian woman at the age of 20 after getting rejected by (by his count) eighth or ninth woman since high school, he decided to look into the research and found it hideously awful. ML’s days of supporting NPR and the ACLU are over, but he’s still fiercely liberal.

Watch for Jocelyn Davis's interview with Cate Terwilliger, co-founder of Gay Pride Colorado Springs, posting later this week.

This type of knowledgeable, rigorous, deep analysis is so often missing from discussions of this topic, making it easy for people to be bamboozled by glib "experts" with fancy titles and big platforms who do nothing but preach dogma. Thank you, ML, for guiding us through the (actual) evidence.

Excellent analysis!

It's bizarre that anyone would quote Chen et Al or Tordoff et Al to show the interventions "work."